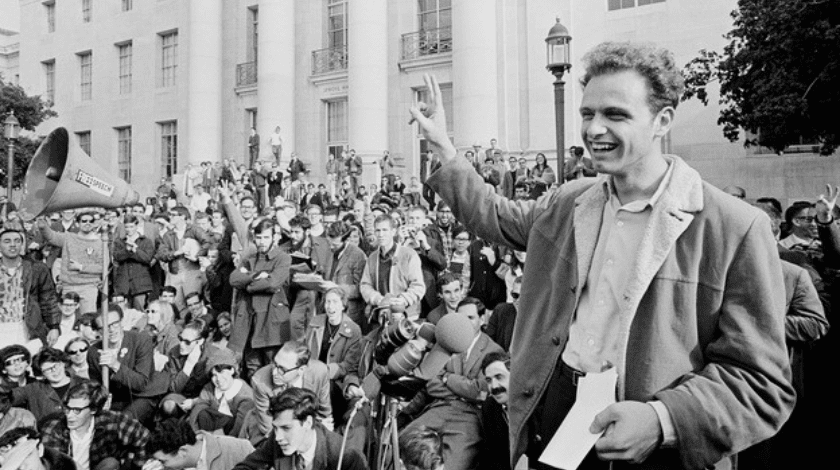

Mario Savio, shown here at a victory rally in University of California, Berkeley’s Sproul Plaza on December 9, 1964.

By Cailyn Nagle

Freedom Summer and the Student Free Speech Movement

In 1964, Mario Salvo stood in front of hundreds of fellow students and said, “And you’ve got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels… And you’ve got to indicate to the people who run it, to the people who own it, that unless you’re free, the machine will be prevented from working at all.” Freshly returning from the Freedom Summer organizing campaign, Salvo and hundreds of other students found they were unable to even pamphlet on their own campuses.

In the first half of the 20th century, colleges viewed themselves as surrogate parents for “children” away from home, a concept known as “loco parentis.” At the time, colleges regulated students’ clothing (particularly for women), behavior, and activities. Fighting alongside the Black community to extend democratic rights under a hostile white supremacist political regime, students spent Freedom Summer facing incredible risk and showing extreme bravery only to arrive back at UC Berkeley and be treated as misbehaving children. With a goal of creating an environment that would allow them to build pro democracy, antiracist, and antiwar movements among their peers, the Student Free Speech Movement took over UC Berkeley. Demanding the ability to organize on campus, students took over Sproul Hall, almost 800 were arrested, and after over a year of fighting they won. It’s easy to conflate a fight for freedom of speech with the newer call for student voice, but Salvo and many others were not throwing their bodies against the gears for an amorphous concept of voice but to build and wield power.

While a voice is a necessary tool to achieve any purpose, conflating a voice with power is like handing someone a hammer to construct a home, then walking away as though they now have a shelter. Without materials, labor, and construction know-how, that hammer isn’t worth a lick of good towards building a house.

Power vs. Voice

“Power” has baggage. There are a thousand axioms that warn about the corrupting effect of it, and even more political science dissertations trying to corral the meaning of it. In 1968 during the Memphis sanitation workers strike, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., defined power as “the ability to achieve purpose, power is the ability to affect change.” While a voice is a necessary tool to achieve any purpose, conflating a voice with power is like handing someone a hammer to construct a home, then walking away as though they now have a shelter. Without materials, labor, and construction know-how, that hammer isn’t worth a lick of good towards building a house.

The Evolution of Student Power

While students have always organized, the victory of the Free Speech Movement opened the door to deeper student driven movements across the country. In 1968, a coalition of Black students occupied North Hall at the University of California, Santa Barbara, (UCSB) securing the creation of the UCSB Center for Black Studies. In 1970, after the Ohio National Guard opened fire on an antiwar gathering at Kent State, killing four students and injuring more, 450 campuses across the nation shut down due to a wave of student strikes in response to the killing. Students self organized into people-powered student unions with the goal of consolidating their collective might to more effectively leverage their needs against the institutional power of campus administrations. Student free speech has taken the form of pamphleting and voter registration, as well as civil disobedience and massive marches. As with any host of movements, some campaigns were strategic and others were not—some campaigns were successful and many were not—but as the front line of social progress, many of the rights and protections we enjoy would not have been possible without these movements.

In 2012, Dreamers across the country led a brave and sharp campaign to force President Obama’s hand on immigration. While the midterm presidential campaign was raging, undocumented youth—often at great personal risk—leveraged the moment to win real gains. As President Obama worked to secure his progressive bona fides leading up to the election against Mitt Romney, undocumented youth began civil disobedience campaigns by occupying Obama campaign offices, which drew contrasts between progressive talking points and progressive action. Though not all of the Dreamers were students, many were. Their brilliant actions at that strategic moment, along with a diversity of tactics and intense organizing, pushed the Obama administration to create the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, which continues to provide an avenue to protect undocumented youth to this day, despite numerous court challenges. DACA was not the end of the fight for justice for undocumented people in the United States, but if the Dreamers had been satisfied with simply having a “voice” in the room it would not have happened at all. The Dreamers successfully built and then wielded power to change the course of immigration policy.

As a former student organizer, who became a community organizer, I find myself in a position my 20-year-old self would find inconceivable—I now sit in a position of power in an institution as a program manager within a foundation. Philanthropy, campus administration, and policymakers have shifted their talking points since I was a youth disrupting Georgia Board of Regents meetings to protest funding cuts. “Student Voice” is everywhere–from the presence of students at academic conferences to speeches at the highest level of higher education—yet student power is a shadow of its former self.

“Voice” without power is a symbol, and if that power does not yet exist, build it and then wield it.

Where Do We Go From Here?

To students: Do not be satisfied with a “voice” at the table unless that voice is proportional representation that allows students to win material gains. “Voice” without power is a symbol, and if that power does not yet exist, build it and then wield it. Learn from the wins and losses of past student movements and embrace the hard work of utopian aspirations with sound strategies in hand.

To those already in the halls of power: College students are adults, let loco parentis die in its previous era with poodle skirts. Students have been on the forefront of social movements both on campuses and off, shaping the world we live in and the movements we strive to support. Students must be active collaborators in work that will shape their future, and we in these positions of security must make room for them as such.

Michelson 20MM is a private, nonprofit foundation working toward equity for underserved and historically underrepresented communities by expanding access to educational and employment opportunities, increasing affordability of educational programs, and ensuring the necessary supports are in place for individuals to thrive. To do so, we work in the following verticals: Digital Equity, Intellectual Property, Smart Justice, Student Basic Needs, and Open Educational Resources (OER). Co-chaired and funded by Alya and Gary Michelson, Michelson 20MM is part of the Michelson Philanthropies network of foundations.

To sign up for our newsletter, click here.